- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

Nautilus International has called for countries such as the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark to re-introduce cabotage laws, after a major new study showed that more than two-thirds of maritime nations around the world have regulations to restrict foreign operations in their coastal trades...

Trade liberalisation, free markets, open competition – that's what the shipping industry is all about, isn't it? Seafarers in many countries have long been told that global business requires them to put up with being undercut by cheaper foreign labour. But new research has revealed that numerous nations are doing just fine with a form of protectionism in their coastal waters.

Described as one of the most comprehensive studies of its kind, the Seafarers' Rights International (SRI) report – Cabotage Laws of the World – provides the first independent analysis of maritime cabotage laws for more than 25 years.

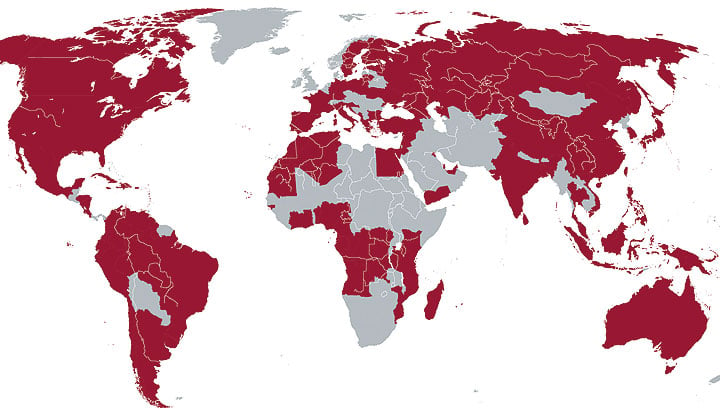

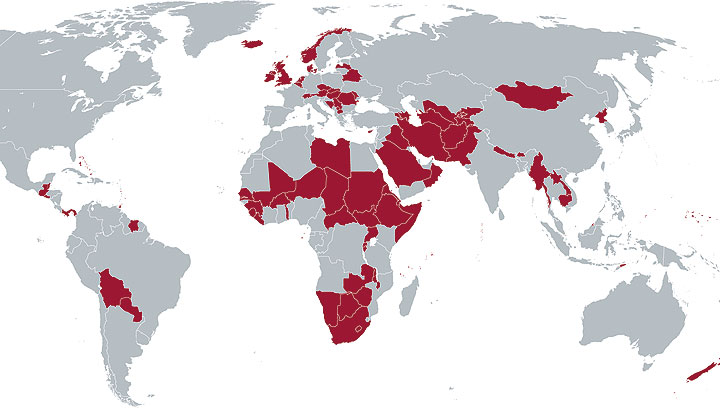

Based on an analysis of legislation and feedback from lawyers in 140 countries, the report reveals that 91 countries – representing 80% of the world's maritime states – have some form of cabotage regulations.

The study says the nature of cabotage laws can vary, but they are usually geared towards: protecting local shipping industries; ensuring the retention of skilled maritime workers and the preservation of maritime knowledge and technology; safeguarding fair competition; promoting safety; and bolstering national security.

It points out that countries have been implementing cabotage policies since the 14th century, and many of the measures now in place around the world date back to laws brought into effect in the 19th century.

The report – commissioned by the International Transport Workers' Federation (ITF) – says there is no single, internationally agreed definition of cabotage and various regional and national laws can refer to terms such as coastal trade, coastwise trade or domestic trade as alternatives.

However, it points out, cabotage is usually understood as covering shipping services between two ports located in the same country or exclusively within a country's territorial waters.

Researchers said previous studies had shown there were at least 33 countries with cabotage restrictions in place in 1920, and at least 40 out of 53 maritime nations had cabotage policies in 1991.

The countries that now have no cabotage restrictions include the UK, the Netherlands, Denmark, New Zealand and South Africa, according to the SRI study.

It says there is a diverse range of restrictions imposed by the 91 countries that have cabotage rules – although they are often linked to requirements to use national-flagged national-crewed ships. 'Reservations regarding the manning of vessels are also common,' it adds.

Cabotage provides jobs for a country's seafarers and safeguards foreign seafarers against exploitation posed by the liberalisation in the global shipping industry, preventing a race to the bottom

.

Some cabotage restrictions are linked to certain trades and services, or certain types of ship, and sometimes it is extended to the exclusive economic zone or the continental shelf.

In many countries, cabotage laws are backed up by penalties, fines, detention and even imprisonment for those who break them.

SRI executive director Deirdre Fitzpatrick said the study aims to fill an important gap. 'For many people maritime cabotage – or coasting, coastwise or coastal trade, as it is sometimes referred to – is understood only vaguely, if at all,' she pointed out.

'This is not surprising as so little is published on the subject. This was a complex project given language and cultural barriers and difficulties in statutory interpretations. But the subject is important. It affects a very wide range of trades, services and activities around the world, with significant social and economic consequences. Policy-makers, especially, need to know more about the subject.'

Nautilus general secretary Mark Dickinson said 'We warmly welcome this report and believe the findings deserve serious attention by all governments and, in particular, other EU member states.

'This thorough and groundbreaking research demonstrates not only the global scale of cabotage protection, but also the strength of the economic and political case for protecting domestic shipping services.

'The reasons why more than 90 maritime nations maintain some form of maritime cabotage law are not hard to see. They are a bulwark against a free-for-all that opens up national services to lowest common denominator competition. They help to protect against an open-coast approach that undermines domestic employment and training, presents a threat to safety at sea, and attacks the principles of national wage rates.

'Any maritime nation serious about its future must have policies in place that help to maintain a sustainable supply of domestic seafarers and a healthy national shipping industry,' Mr Dickinson noted. 'Cabotage protection helps to safeguard those precious resources by staving off damaging deregulation and guarding against the excesses of exploitation in the globalised shipping industry.

'Our Jobs, Skills and the Future report highlighted the need for the UK – as an island nation with a huge reliance upon a strong and viable domestic shipping fleet - to adopt an ambitious policy programme that will give the country the shipping industry, and the seafaring workforce it needs for the future. Cabotage will help to deliver that.'

David Heindel, chair of the ITF seafarers' section commented: 'The lack of accurate facts on cabotage laws around the world has been an impediment for policy-makers considering implementing cabotage laws This report represents a circuit breaker, providing policy-makers with the relevant facts for proper decision-making.

'The SRI report debunks the myth that cabotage is an exception not the rule,' he pointed out. 'We know there are a number of countries considering introducing, strengthening or diminishing cabotage regulation. This report will assure those governments that it makes sense to enforce national cabotage laws.'

James Given, chair of the ITF's cabotage task force, added: 'The benefits of cabotage laws are self-evident. For countries that depend on the sea for their trade, cabotage safeguards their strategic interests as maritime nations, bringing added economic value while also protecting national security and the environment.

'Cabotage provides jobs for a country's seafarers and safeguards foreign seafarers against exploitation posed by the liberalisation in the global shipping industry, preventing a race to the bottom.

'Without strong cabotage rules local workers often have to compete with cheap, exploited foreign labour on flag of convenience vessels, the owners of which usually pay substandard ages and flout safety laws.'

Tags