- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

The Dutch maritime authorities have raised safety concerns around vessels operating near North Sea wind turbines – and their research could prompt a rethink of navigational procedures in crowded seaways. Andrew Linington reports

Seafarers are facing a growing challenge to navigate safely in the North Sea as ships are forced to compete for space with an increasing number of windfarms, oil platforms and other 'industrial' developments.

That is the conclusion of research carried out by the Dutch Safety Board in response to several collisions and allisions between ships and structures such as wind turbines. The Board argues that officials have set 'unrealistic' safety buffer zones around windfarms based on inadequate understanding of actual risks – leaving large vessels with insufficient room to manoeuvre in an emergency.

'Up to now, the consequences have been limited to material damage, but more serious human and environmental consequences are a realistic possibility,' the study warns.

With significant new developments planned in the North Sea, the Board calls for a rethink of risk management and suggests that seafarers may need to change the way in which they navigate in the area.

Increasing pressures

The Dutch Safety Board report – titled Compromise on Room to Manoeuvre – points out that the North Sea is already one of the busiest waterways in the world, with some 240,000 shipping movements a year in the Dutch section alone.

Climate change means ships are facing growing risks of extreme conditions in the North Sea, and consequential pressures to change course or to remain at sea rather than entering port may lead to increased vessel traffic density in key areas, the report notes.

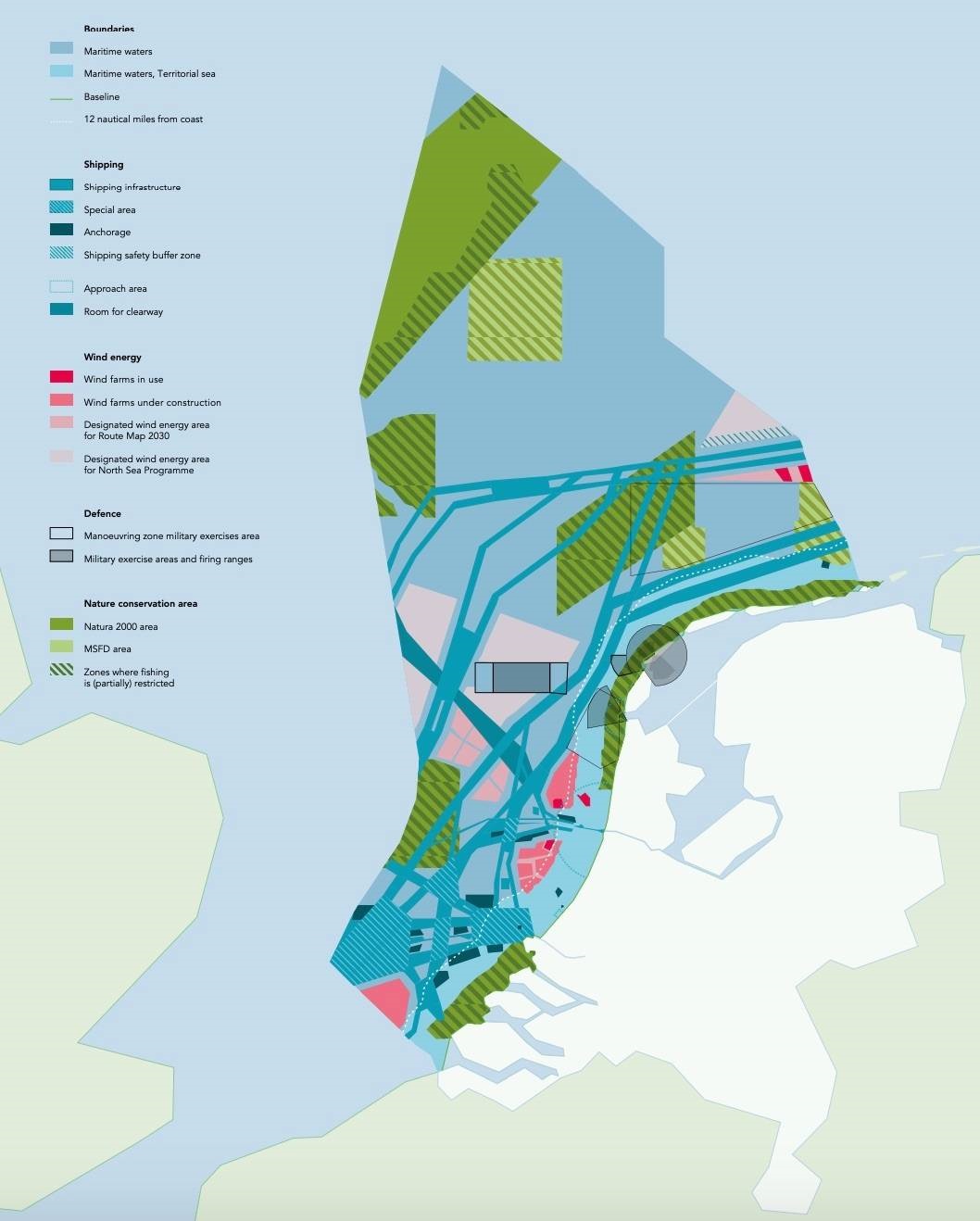

But free space for shipping is coming under increasing pressure, it warns. The Dutch section of the North Sea already has six windfarms, 700 wind turbines, 7,000km of subsea piping, 4,000km of cables and 160 oil and gas production platforms, as well as naval exercise areas and nature reserves. A further 1,000 wind turbines are due to be added by 2031, and there are also plans for storing CO2 and generating solar power, hydrogen and ammonia in the North Sea.

Inadequate risk management

Risk management in the area is failing to keep up with the pace of developments, with many measures being outdated or based on inadequate or over-generalised criteria.

Existing policies display 'insufficient understanding of the risks to shipping safety when positioning wind farms', and there are significant 'knowledge gaps' in such subjects as the effects of collisions, the effectiveness of measures to prevent collisions, and the behaviour of vessels in certain circumstances.

Most current and planned windfarms are adjacent to traffic separation schemes, the report points out. The 'buffer zone' that seeks to reduce the risk of collisions and allisions sets a distance of 1.87nm on the starboard side and 1.57nm on the port side of a shipping lane, with a formula based on a notional six ship lengths to complete a 360-degree turn.

However, simulations undertaken for the Safety Board showed that the 1.87nm buffer zone is not sufficient for wind-sensitive and heavy vessels such as ultra-large containerships in conditions commonly encountered in the North Sea.

'This is understandable because the design criterion takes no account of the influence of hydrological, hydrodynamic, and meteorological conditions on vessels' manoeuvring characteristics,' the report stresses.

Problematic monitoring proposals

The Safety Board also challenges proposals to introduce a system of vessel traffic monitoring (VTM) – as opposed to vessel traffic services (VTS) – to cover shipping operating around windfarms. VTM is reliant upon a single operator monitoring several different windfarms, and would fail to address the risk of ship-to-ship collisions, the report says. The proposed system could also cause confusion among ship crews because it deviates from international standards and will not appear on nautical charts nor come with reporting requirements.

The report says the Dutch government sees emergency towing vessels (ETVs) as an important control measure. However, it cautions, their effectiveness is constrained by factors such as positioning, availability, reliability, bollard pull and the challenges of establishing a towing connection in poor conditions.

International safety review required

The Safety Board says a radical revision of safety management in the North Sea is required to reflect developments in shipping and the growing pressures for space. It argues for a comprehensive assessment of the use of the North Sea and the impact upon shipping, with modelling applied to new and existing installations and used to produce more realistic safety goals.

It also urges the Dutch government to work with other North Sea nations to secure modified global standards that reflect a better understanding of shipping safety risks, and to submit proposals for new International Maritime Organization rules.

'An internationally shared view on how shipping can navigate safely around fixed objects is crucial,' the report stresses.

Actions for seafarers

The Safety Board says ships need to change the way they operate in the increasingly crowded North Sea, and in a new Shipping Occurrences report it calls for seafarers to consider ways they can 'prepare for confronting the impact' of an 'increasingly dynamic and complex' vessel traffic scene in the area.

'For shipping, this means that vessels will operate closer to windfarms and closer to one another,' the Board notes. 'As a result, the North Sea increasingly resembles a narrow waterway or the approach area to a port. Less and less space is available to cope with problems such as a blackout or to ride out a storm. Certain course changes – for example to keep the vessel's head on to the waves – are becoming more difficult to execute.'

All this means that crews need to properly plan before entering the area, with an assessment of location-specific conditions and associated risks, it says.

When in shipping lanes passing windfarms, ship masters should consider operating their vessel as if it was approaching a port, the Board suggests. 'That includes having a different personnel setting on the bridge, keeping the engineroom manned, and making sure that propulsion and multiple steering gear options are immediately available.'

Captains, shipping companies and cargo planners should also cut ship speeds in congested areas, enabling more time and space to be given to anticipate potentially dangerous situations and take timely action, the Board concludes.

Case study: Julietta D

One of the incidents which led to the Dutch Safety Board report involved the Maltese-flagged bulk carrier Julietta D, which began to drift off the Dutch coast when its anchor failed to hold in stormy conditions in January 2022.

The ship's engineroom was holed when it hit another vessel before drifting into a windfarm under construction and striking a turbine and other structures. It was abandoned and was eventually towed into the port of Rotterdam by the Dutch-owned tug Sovereign.

An investigation highlighted the problems associated with the choice of a safe anchorage and the challenges faced by the tug in securing a towing connection, as two crew members suffered serious injuries when a wave swept over the main deck as they were returning to their accommodation. Dropping the ship's other anchor would have posed a threat to the crew in the prevailing conditions and would have also run the risk of damaging submarine cables and pipelines in the area, investigators said.

The report's recommendations included a call for windfarm developers to explore and study the possibilities to install innovative physical barrier systems to prevent allisions with critical windfarm structures, noting that there had been some 'promising' early research into such technology.

Image: The Maltese bulk carrier Julietta D drifted into a windfarm under construction. Image: KNRM

Tags