- Topics

- Campaigning

- Careers

- Colleges

- Community

- Education and training

- Environment

- Equality

- Federation

- General secretary message

- Government

- Health and safety

- History

- Industrial

- International

- Law

- Members at work

- Nautilus news

- Nautilus partnerships

- Netherlands

- Open days

- Opinion

- Organising

- Podcasts from Nautilus

- Sponsored content

- Switzerland

- Technology

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

- Welfare

With more people looking to work beyond the state retirement age, employers must do more to achieve equal opportunities in employment for all seafarers, says Nautilus Council member Malcolm Graves

I am a Master Unlimited, with over 52 years' experience of the shipping industry and a concurrent 36-year career in the Royal Naval Reserve.

Working into retirement was top of my six-point statement to members that supported my election to the Nautilus Council in June 2019. The issue for Council's attention was 'to combat industrial age discrimination, to achieve equal opportunities in employment, regardless of perceived length of service remaining'.

The phenomenon of employing older people in the UK arises today mainly through the Equality Act of 2010, which no longer specifies a particular age when people must retire.

An increase in the state pension age reflects improved life expectancy and hence the prospect of and need to provide for longer retirements.

With more employees depending upon 'defined contributions' pension schemes, which provide an income in retirement based on the amount you pay in, the fund's investment performance and the choices you make at retirement, some people may choose to defer their pensions and remain in employment, until the market would be right for them to purchase an annuity.

After all, it is likely to be now a distant memory when, through an employer's goodwill, a long serving seafarer might be rewarded with a promotion and an enhanced pension, prior to retirement!

Apart from obvious financial considerations, many professional seafarers who have committed a high proportion of their lives to seafaring could find it particularly hard harmonising with life's rhythms ashore, for any length of time. In such cases, it could be said, 'the sea always calls back its own'.

Naturally, such decisions must be tempered with important family and home considerations, which change as one grows older, before a return to sea would be practicable.

Protected characteristics

So, what should an older person be entitled to expect in the workplace? Intelligent management and respect, one might suggest.

Management should ensure the practical application of fairness, within an Equality, Discrimination, and Inclusion (EDI) Policy, based on the Equality Act of 2010. Under the Act, 'Age' is top of the nine protected characteristics. So senior officers and shipboard heads of department should be trained and updated regarding the necessary implications of managing 'seniors' accordingly.

Naturally, such a statement should be included in an employee's terms and conditions, and the full EDI policy should be available either online or from management upon request. If any person is unhappy with the provisions, or absence of such a policy, then the matter should be referred to their industrial representative and union for advice.

I feel that suitable candidates in each protected characteristic should be assigned equal importance within an organisation; so gender should not prevail over age, for instance.

All seafarers entering their working environment are entitled to a committed policy of dignity and mutual respect from colleagues and, ultimately, from their employer.

Sea staff should be made aware of the Bullying and Harassment Policy adopted by their employer. If none should exist, then it is possible management could be provided with the principles of such a policy, through those seafarers' unions that share a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with them.

Equal opportunities

As mentioned, I feel that people working beyond the state retirement age should be allowed equal opportunities in employment, regardless of how long they might be expected to remain in an organisation. Therefore, the meaning of such 'equality' should include a reasonable expectation of promotion, rooted within the ethos of an organisation.

From my own experience, feelings of being undervalued by the employer could arise where individuals are denied courses such as 'Building on potential' that could assist in their lifelong career development.

Also, a person in a higher age category could be marked down unfairly at interview, possibly through a mistaken perception of how many years' service that individual could give, in comparison with a younger candidate. It can be frustrating and possibly distressing for an individual whose experience and superior qualifications are discounted through age prejudice in such cases.

Furthermore, within a recruitment and interview process, the relative strengths and abilities of competing candidates could be assessed against person specification criteria. Thus, rating the suitability of each through merit.

However, more subtle considerations could impact upon the outcome.

The relative cost in employing different candidates could be another factor in appointments. This means that a new entry candidate, recruited near to the lowest rate for the job, might be preferred to a fully qualified candidate, with long service in the same organisation, who could cost thousands more to promote.

Such criteria should not be included in a choice of candidate based on merit alone, but how can this be denied? To add insult to injury, the employer might then expect the more experienced person to familiarise their newly appointed line manager with important aspects of the job.

Such experiences are likely to have been tolerated, or otherwise by persons in a higher age category, through factors beyond their control which is unfair, and this fact should be recognised.

Examples of thoughtless, disrespectful comments made by persons towards a 'senior' such as 'You are not still here?' and 'When are you going to retire?'

An example of behaviour towards a 'senior' that could breach the relevant policy on mutual respect is a younger master trying to chase the other up the stairs to the bridge. Quite bizarre!

Career ambitions

I would suggest responsible persons should be appointed with the experience to manage older, more 'senior' persons onboard, within the provisions of the Equality Act.

Unfortunately, due to recruitment policies such as those alluded to above, the maturity of understanding in officers managing 'seniors' is often absent, which is unjustifiable. Thus, there should not be a presumption that older people would never be interested in suitable training opportunities and possible promotion. Instead, there should be an appraisal procedure, fit for purpose, to record and properly act upon their aspirations.

In this respect, a more diverse range of ages across an organisation should be demonstrated by employers, to include those positions held by more senior officers.

The case for continuing to employ older persons at sea should include the benefits of their long experience and advice which would be available to the master and to others, possibly through mentoring.

The experience of 'seniors' could allow different perspectives to certain job procedures which could be valuable.

For instance, in an age where increasing reliance has been placed upon GPS, electronic charts, integrated navigation and dynamic positioning systems, familiarity with how to revert to basic principles navigationally should be very valuable.

In such cases, older members of staff on a dynamically positioned ship who are experienced in fixing the position with a sextant would be able to impart such skills to cadets and others. Similarly, to describe how certain vessel operations could be conducted, with just a single screw and azimuth thruster.

In addition, the benefits to a UK organisation employing older people should include a saving in employees' National Insurance contributions. You don't pay National Insurance if you work past state pension age.

For the employee, the advantages of working beyond retirement age, apart from financial, would include opportunities for professional updating and in relating better to mentees.

The disadvantages of employing people beyond retirement age would vary according to the nature of the job onboard, but the risk of personal injury could be higher, so employers might be best advised to discuss this matter with their respective P&I club representatives, to ensure adequate personal injury cover for all mariners.

All concerned should properly consider and comprehend what is meant by discrimination towards older people. From the foregoing, clearly this is an area of the UK Equality Act 2010 requiring a meticulous, forensic look at where discrimination could occur.

Otherwise, those discriminated against would be denied the necessary protection deserved and employers, who are unable to resolve such issues could risk a legal claim for discrimination.

The wisdom inherent in equality and diversity concepts should be recognised and accepted. This includes the understanding that an organisation can be strengthened through the wider range of experiences and abilities contributed by a more diverse workforce.

There is the need for proper respect towards 'seniors', some of whom may have held commands previously. An older seafarer should not be pre-judged solely on age but through what that person is able to contribute.

As every good performer should know, there is clearly a time to 'leave the stage'! However, there are recognised criteria for judging continued fitness and job performance standards.

I would suggest any capability procedure should not be manipulated to precipitate subject failure, where implemented by an employer. If so, the standing joke could arise that an individual's critics have all left the organisation, long ago, while the one highlighted for alleged failings is still there!

Case studies

Captain Johan Kooij

Captain Johan Kooij's love of seafaring and opportunities from industry contacts brought him out of retirement several times, until he reached an agreement with his wife at age 72 to finally retire from a life at sea.

At aged 58, he could officially retire from his job in the Netherlands, but his employer said to him 'you are not going to retire,' to which Capt Kooij replied, 'I am not planning to.' From age 58-66, he worked on double pay, the reasoning being there was a shortage of captains, especially captains in heavy lift shipping.

Capt Kooij's main reason for working through retirement was that he really enjoyed his job: 'The long voyages, being on the bridge wing, watching the stars. I was standing on the bridge looking around and thinking, "Hey, you are getting paid, enjoying yourself."'

His advice for those considering working into retirement: 'If you are not blocking the promotion from younger officers, then why not keep working for a couple of years? As long as you feel fit enough and able, I don't see no reason why you should stop.'

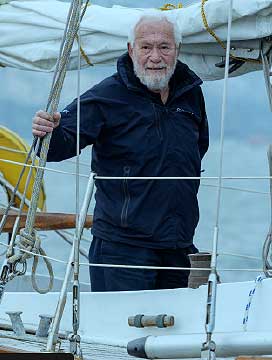

Sir Robin Knox-Johnston

Sir Robin Knox-Johnston began his career at sea in the Merchant Navy, working his way up to master level as well as completing solo sailing trips around the world. Both in his youth and again at aged 68, he set the record for the oldest yachtsman to complete a round the world solo voyage in the Velux 5 Oceans race.

On his first solo sailing trip as the first man to sail solo and non-stop around the globe in 1968/69, he was told it couldn't be done, and the same was said in 2007. 'Youngsters would say you are too old to do this, and that's absolute rubbish. They would say you could never manage one of these boats; yes I could, and I proved them wrong.'

His advice to people wanting to work through retirement: 'I would say to people, if you feel fit and want to work beyond retirement age, why don't you? You have qualities and experiences that would be very good for business or whatever your particular task is.'

At the time of writing, Sir Robin was working towards the Clipper Race which is due to take place in February 2022, Covid travel requirements allowing.

Anthony Stevens

Senior purser Anthony Stevens, 73, has had a varied career across several sectors in the maritime industry, from cruiseships and ferries to serving during the Falklands War.

His final appointment was working with the royal research group managed by the National Environmental Research Council as a purser until he retired from full-time work at age 70.

Since then, he has worked as a relief purser. 'When you have had a lifetime and career like I have being a purser, which is like the front of house of a passengership, you can't just become a recluse.'

Mr Stevens talks about the worries and views of society that have affected him on working into retirement: 'I think there is a certain stigma attached to being retired, that you become a drain on resources. Old people need more healthcare, so their personal needs increase in retirement. I think a lot of people don't think that one day they will be like that and I think that can be a drain on mental health of people that are retired. This view of not being wanted by society anymore can affect mental health, and I have those thoughts myself. I think there are definitely mental health issues that haven't been talked about before.'

Tags

More articles

The future for seafarer pensions?

Paid annual leave for part-time seafarers – how a new ruling affects members

How to be menopause savvy

In recognition that over half the workforce will go through menopause during their working life – some for between two and 15 years – industry body Maritime UK launched a Menopause Hub. The online portal will be launched on International Women's Day 8 March 2022.